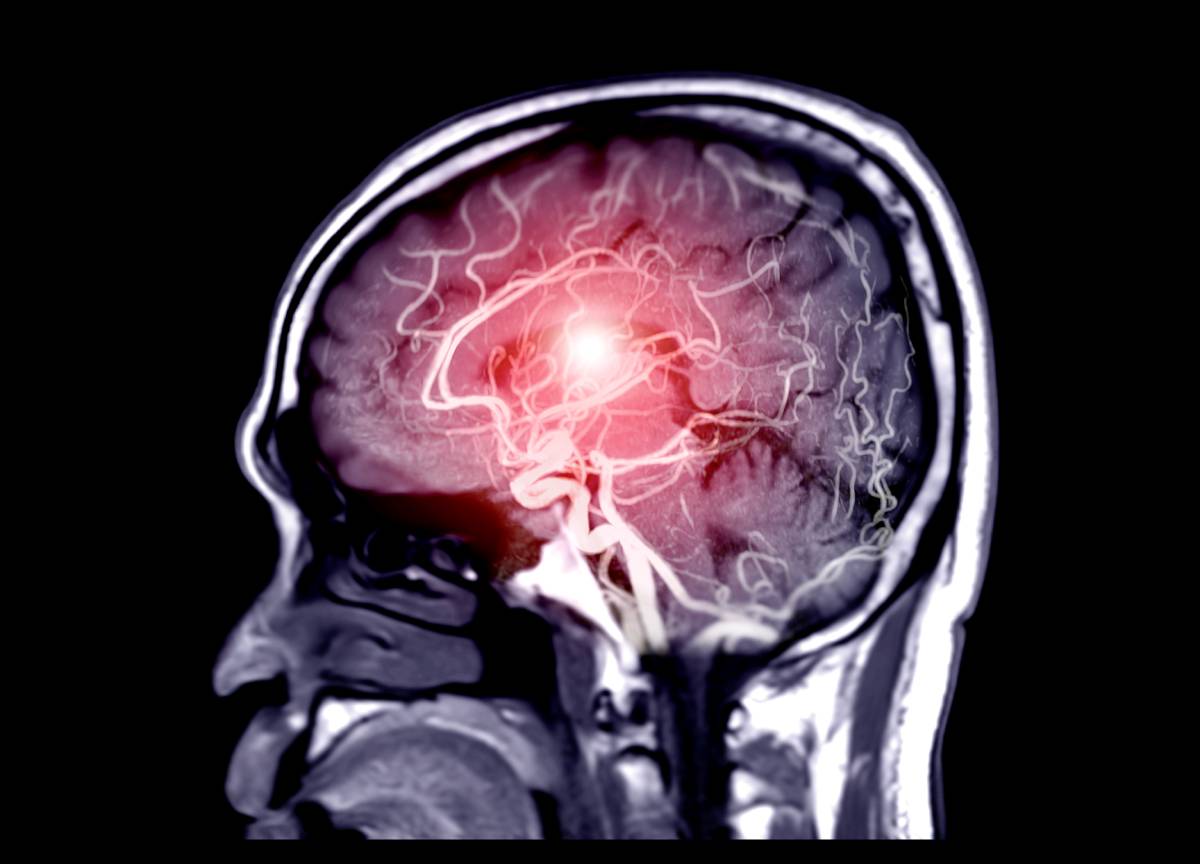

Acute ischemic stroke occurs because of decreased blood flow to the brain, resulting in neuronal cell death. In patients with ischemic stroke, recanalization of the occluded (blocked) vessel, known as endovascular therapy, helps to reduce cell death and improve patient outcomes [1]. Endovascular treatment, when done correctly, can restore blood flow within minutes and is now recognized as one of the most powerful treatments in the field [2].

When looking at anesthesia for endovascular stroke treatment, the two most used techniques are moderate conscious sedation and general anesthesia with intubation [3]. Due to shorter procedure times and long-standing use, general anesthesia is the preferred method in clinical spaces. On the other hand, conscious sedation and local/regional anesthesia allow anesthesiologists to monitor neurologic status simultaneously. Some studies have also indicated conscious sedation may be associated with better hemodynamic stability compared to general anesthesia [4]. A systematic review isolated nine studies (1956 patients total) and compared results between these two techniques. During endovascular intervention, patients under general anesthesia had a higher risk of respiratory complications and death, as well as lower odds of good functional and angiographic outcomes during post-op. However, the authors caution that, although the evidence seems to strongly support the use of conscious sedation over general anesthesia during endovascular stroke treatment, the difference in stroke severity at onset may significantly confound the comparison [4].

After recognizing the potential complications and adverse outcomes associated with general anesthesia, researchers from Emory University performed a retrospective study assessing the use of the α2 adrenergic agonist dexmedetomidine during anesthesia for endovascular stroke treatment. The main appeal of dexmedetomidine is its ability to provide sedation without respiratory depression [5]. Additionally, patients sedated with dexmedetomidine are easily aroused with voice stimulation, making this sedative a prime candidate during procedures involving sophisticated neurological testing [6]. Among 216 patients, 2 groups were derived: those receiving GA (general anesthesia) and those receiving DEX (dexmedetomidine). The GA group was slightly older and had slightly less severe strokes; otherwise, patient characteristics were very similar. After analysis, it was found the GA group experienced more hypotension, greater variation in blood pressure, and a greater need for vasopressors [6]. DEX was associated with better functional outcomes, as assessed by scores on the NIH stroke scale (NIHSS).

The most fundamental endovascular treatment for acute ischemic stroke is intravenous tissue plasminogen activator (IV t-PA); however, less than 40% of patients regain functional independence using this technique alone. Mechanical thrombectomy using a stent-retriever, in addition to IV t-PA, increases reperfusion rates, improving long-term outcomes [7]. A meta-analysis found patients undergoing this procedure fare better under conscious sedation/local anesthesia, as opposed to general anesthesia, similar to the findings from IV t-PA alone. GA was associated with poorer functional outcome and a slightly lower rate of good neurological outcome; however, the two anesthetic methods yielded similar rates of vascular complications [8].

Studies discussing anesthetic considerations for endovascular stroke treatment seem to highlight the pitfalls of general anesthesia and support the use of alternative sedation methods, such as conscious sedation, local/regional anesthesia, or certain agents such as dexmedetomidine. The biggest limitation for studies in this area comes from their retrospective nature; randomized, high-powered studies that can stratify patients based on stroke location and severity would improve the extant literature.

References

- Walter, K. (2022). What is Acute Ischemic Stroke? JAMA, 327(9), 885. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2022.1420

- Nogueira, R. G., & Ribó, M. (2019). Endovascular Treatment of Acute Stroke. Stroke, 50(9), 2612–2618. https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.119.023811

- McDonagh, D., Olson, D., Kalia, J., Gupta, R., Abou-Chebl, A., & Zaidat, O. (2010). Anesthesia and Sedation Practices Among Neuro-interventionalists During Acute Ischemic Stroke Endovascular Therapy. Frontiers in Neurology, 1. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fneur.2010.00118

- Brinjikji, W., Murad, M. H., Rabinstein, A. A., Cloft, H. J., Lanzino, G., & Kallmes, D. F. (2015). Conscious Sedation versus General Anesthesia during Endovascular Acute Ischemic Stroke Treatment: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. American Journal of Neuroradiology, 36(3), 525–529. https://doi.org/10.3174/ajnr.A4159

- Whalin, M. K., Lopian, S., Wyatt, K., Sun, C.-H. J., Nogueira, R. G., Glenn, B. A., Gershon, R. Y., & Gupta, R. (2014). Dexmedetomidine: A Safe Alternative to General Anesthesia for Endovascular Stroke Treatment. Journal of NeuroInterventional Surgery, 6(4), 270–275. https://doi.org/10.1136/neurintsurg-2013-010773

- Mack, P. F., Perrine, K., Kobylarz, E., Schwartz, T. H., & Lien, C. A. (2004). Dexmedetomidine and Neurocognitive Testing in Awake Craniotomy. Journal of Neurosurgical Anesthesiology, 16(1), 20–25. https://doi.org/10.1097/00008506-200401000-00005

- Saver, J. L., Goyal, M., Bonafe, A., Diener, H.-C., Levy, E. I., Pereira, V. M., Albers, G. W., Cognard, C., Cohen, D. J., Hacke, W., Jansen, O., Jovin, T. G., Mattle, H. P., Nogueira, R. G., Siddiqui, A. H., Yavagal, D. R., Baxter, B. W., Devlin, T. G., Lopes, D. K., … Jahan, R. (2015). Stent-retriever Thrombectomy After Intravenous t-PA vs. t-PA Alone in Stroke. New England Journal of Medicine, 372(24), 2285–2295. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1415061

- Brinjikji, W., Pasternak, J., Murad, M. H., Cloft, H. J., Welch, T. L., Kallmes, D. F., & Rabinstein, A. A. (2017). Anesthesia-related Outcomes for Endovascular Stroke Revascularization. Stroke, 48(10), 2784–2791. https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.117.017786